Preserving representation: artistic license in the Steven Universe fandom

It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that Steven Universe, ostensibly just another cute, fantastical offering from Cartoon Network, has spent the two years of its broadcast upending the status quo of American children’s cartoons. The diversity of skin color and body type in this show, not to mention its canonical representation of queerness, gender non-conformity, and mental illness, are phenomenally affirming for many demographics and communities*, but as a neurotypical white cis girl who frankly does not need any more validation from the entertainment I consume, I personally value Steven Universe for an additional reason: it’s the first cartoon, or piece of media in general, that has inspired me to draw fanart.

It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that Steven Universe, ostensibly just another cute, fantastical offering from Cartoon Network, has spent the two years of its broadcast upending the status quo of American children’s cartoons. The diversity of skin color and body type in this show, not to mention its canonical representation of queerness, gender non-conformity, and mental illness, are phenomenally affirming for many demographics and communities*, but as a neurotypical white cis girl who frankly does not need any more validation from the entertainment I consume, I personally value Steven Universe for an additional reason: it’s the first cartoon, or piece of media in general, that has inspired me to draw fanart.

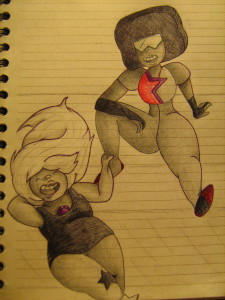

That might not sound significant—the SU fandom is enormous and unceasingly active online, boasting thousands upon thousands of fan artists and fanfiction writers who greatly surpass me in talent and dedication—but even my passive engagement with this community has opened my eyes to my artistic limitations. Before I started sketching Garnet and Amethyst over the summer, I had rarely attempted to draw body fat, or full lips, or even textured hair. Getting a handle on the designs of my favorite characters has been a rewarding process that, in my opinion, illustrates just one example of representation’s positive impact even on more privileged consumers of media.

The Steven Universe creators (affectionately called the Crewniverse) encourage fan speculation and experimentation; for instance, in response to questions about characters’ relationships and romantic orientations, they have clarified canonical details while giving fans free rein to interpret and innovate as they wish. Presumably, this applies to visual representations of identity as well—or does it?

At first glance, why not? In the world of Steven Universe, the magical beings known as Gems are humanoid in appearance yet concretely established as an alien species with no particular attachment to human concepts of gender or race. Fan artists therefore have a great degree of creative freedom in how they choose to draw characters, especially in human AUs (alternate universe narratives): various artists have translated Jasper’s red-on-orange stripes into vitiligo, Peridot’s triangular hairstyle into a hijab, and Opal’s forehead gem into a bindi. And, of course, humanizing a red or blue alien opens up an entire spectrum of skin colors.

Problems arise, however, when artists takes a subtractive rather than additive approach to representation. This occurred recently with fanart of the major character Garnet, who is clearly coded as a strong, beautiful black woman: she is dark-skinned and curvy, with a large afro and distinctly non-European facial features. In August, an illustration of a white, blond version of Garnet with the faux-inspirational caption “Anyone can draw anything!” made the rounds on Tumblr, sparking intense controversy over the truths and fallacies contained within this message. In a literal sense, it’s true—no one can prohibit a fan artist from lightening a character’s complexion, any more than one can physically restrain another from voicing prejudiced opinions. And no, fan-produced content will never nullify or replace canon. But that doesn’t make the content, let alone this line of reasoning, any less disrespectful to the spirit of the show or any less harmful to those fans who find genuine empowerment in representation of their identity. Mainstream media is already choked and clogged with whiteness; why go and smear that all over a cartoon that has the integrity to reflect real-life diversity?

While depictions of a whitewashed Garnet, a slimmed-down Rose Quartz, or a heteroromantic Pearl are not particularly difficult to find, nor, fortunately, are they immune to criticism. Less fortunately, because of the nature of Internet discourse, for every misguided artist who accepts and internalizes a thorough critique, another contends with a violent backlash entirely disproportionate to their initial misstep; and for every purveyor of death threats who goes unchallenged, a reasonable critic of identity erasure faces paradoxical accusations of bigotry. Even for a non-account-holder like me who merely observes from the sidelines, sifting through the vitriol in search of compelling arguments can be an overwhelming task**.

Ultimately, what I took away from this debate/debacle was not a drastically altered view on representation in fandom, but rather a deeper understanding of my own perspective and the means to articulate it. Honoring existing representation is one way to celebrate diversity in fictional media; re-imagining or “headcanoning” characters as members of other marginalized identities is another. But treading the same tired path of invoking freedom of expression to reinforce the societal status quo? That’s not how I choose to engage with my favorite show, and it’s not how I intend to treat the characters I love.

* For more in-depth discussions of representation in the show itself—especially regarding its queer themes—I recommend “‘Steven Universe’ and the Importance of All-Ages Queer Representation” from Autostraddle, as well as various articles in the SU tag on Bitch Flicks.

** At one point, multiple people were arguing that (a) Garnet is not actually black and (b) interpreting a nonhuman character as a person of color is automatically racist. The best rebuttal I’ve seen comes from Tumblr user passionpeachy, in this pair of posts.

Elise Berendt (SC ’17) is a Hispanic Studies and Linguistics major from Pleasanton, California.

![[in]Visible Magazine](https://community.scrippscollege.edu/invisible/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2011/04/Invisible-Masthead-2011-Spring1.png)

Comments are closed.