Cultural Dimensions of Personal Space

For the first few weeks of my study abroad experience in Salamanca, Spain, even amidst a whirlwind of orientation activities, I found it relatively easy to forget that I was living in a different country—an entirely different continent, even—from the one in which I’d previously spent my entire life. Of course, I don’t pass as a native Spanish speaker, and I have yet to master the intricacies of the Spanish meal schedule, but, particularly as a student living in the dorms rather than with a host family, I certainly wasn’t complaining of any culture shock. It wasn’t until I participated in my first group intercambio—a language-exchange meetup, in this instance between my program classmates and University of Salamanca students—that I noticed one major discrepancy between Spanish and American social norms.

For the first few weeks of my study abroad experience in Salamanca, Spain, even amidst a whirlwind of orientation activities, I found it relatively easy to forget that I was living in a different country—an entirely different continent, even—from the one in which I’d previously spent my entire life. Of course, I don’t pass as a native Spanish speaker, and I have yet to master the intricacies of the Spanish meal schedule, but, particularly as a student living in the dorms rather than with a host family, I certainly wasn’t complaining of any culture shock. It wasn’t until I participated in my first group intercambio—a language-exchange meetup, in this instance between my program classmates and University of Salamanca students—that I noticed one major discrepancy between Spanish and American social norms.

Scene: interior of a dim but inviting brick-walled tavern, 10 p.m. Our intercambio group dominates the back of the restaurant, positioning ourselves in clusters of three or four around the long tables lined with a selection of traditional tapas. As I tune out, for just a moment, from the conversation between two Spaniards and a fellow U.S. student, I realize that I can’t breathe. Why, exactly, are we standing so close together? The building isn’t that loud. Perhaps it’s just my neurotic inability to maintain eye contact and inhale at the same time, but come on now—we’re huddled close enough to be hashing out (American) football plays, rather than sharing travel anecdotes. Surrounded by three people taller than myself, I find my neck aching with the simple effort of listening.

The rules and even definition of personal space differ greatly across cultures, but with so many social continuities between Spain and the U.S., I didn’t see this one coming. As it turns out, Spanish people like to get close during casual conversations. It’s also true that greetings often take the form of two kisses on, or more accurately parallel to, the cheek. However, what initially surprised me most about this comfortable intimacy between brand-new acquaintances is that it doesn’t hop the gap to complete strangers. A quick introduction is seemingly all it takes to graduate to a level of casual physical contact, but in its absence, Spaniards may act aloof or inconsiderate by American standards. Bump into someone on the sidewalk? Keep quiet and keep walking; with streets this narrow it’s only to be expected. And (my personal favorite as an introvert) forget about wishing a buen día to the unfamiliar people you pass on the way to school or work; apparently in some cases even smiling at a stranger may come off as flirtatious.

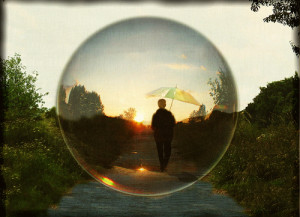

So, where exactly does the personal bubble begin and end? It’s actually not as contradictory as it sounds, if you’re willing to collapse the distinctions between private/public and individual/social life onto more or less a single axis. In Spain, nearly all social interaction takes place in public spaces—cafés, parks, bars—that allow for loud conversation and bonding over drinks or tapas. Many young people live with their parents, and dorm culture, while not asocial, doesn’t really support hanging out with friends in a room, let alone hosting a larger party. Alone or not, if you’re out in public, you’re subject to the rules of social engagement, complete with a much tighter personal radius than is typical in America.

I can’t say from experience how this plays out in a larger city like Madrid, but in Salamanca, fortunately, personal safety is not an enormous concern. Even those of my classmates who spend each weekend immersed in the local nightlife report feeling secure walking back to their homes in the early hours of the morning, and none of the women in our group have complained of street harassment.

On the other hand, according to my classmates, the homestay experience takes some of the privacy out of private life, beyond the obvious shared mealtimes. Quite a few Spanish host mothers like to enter their students’ rooms during the day to clean and even rearrange their space, and one friend recently moved from a house into the dorms amidst her mother’s harsh judgment of her schedule and lifestyle. One week after the switch, she tells me it’s an immense relief to be living on her own terms.

Even without the forced sociability of a homestay, I’ll likely blunder my way through many conversations over the course of my transition into Spanish life, but I’m grateful for the forgiving social atmosphere that will attribute my errors to caution or excessive politeness rather than brashness—an accurate assessment of both my preference for the formal register and my tendency to overestimate the boundaries of others’ personal bubbles. Space, while more objectively universal than time, still exists at the mercy of culture and is subject to manipulation within the social dimension. Direct comparison of its cross-cultural treatment, even between two modern industrialized societies as similar as Spain and the United States, highlights intriguing differences in conceptions of individual and group identity.

![[in]Visible Magazine](https://community.scrippscollege.edu/invisible/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2011/04/Invisible-Masthead-2011-Spring1.png)

Comments are closed.