The Fault in Our Stars: Thriving With Cancer

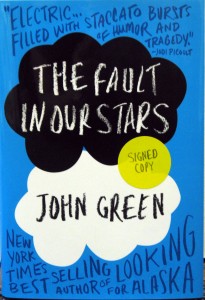

It’s very hard to be a critical reader when experiencing a story is no longer about the fiction itself and is instead a reflection of personal experience. New York Times best-selling author John Green knows how to transform a reading experience into a highly personal one. Known for his books such as Looking For Alaska and Paper Towns, Green is a master of taking teenage life and connecting it to classic poetry, and more importantly, to the poetic aspects of everyday life. His latest book, The Fault in Our Stars is no exception. If anything, The Fault in Our Stars (TFIOS) is the quintessential example of how to transform a literary experience into one that is first and foremost deeply personal.

It’s very hard to be a critical reader when experiencing a story is no longer about the fiction itself and is instead a reflection of personal experience. New York Times best-selling author John Green knows how to transform a reading experience into a highly personal one. Known for his books such as Looking For Alaska and Paper Towns, Green is a master of taking teenage life and connecting it to classic poetry, and more importantly, to the poetic aspects of everyday life. His latest book, The Fault in Our Stars is no exception. If anything, The Fault in Our Stars (TFIOS) is the quintessential example of how to transform a literary experience into one that is first and foremost deeply personal.

TFIOS was a step in a new direction for Green, as his first young adult novel with a female protagonist and narrator who does not fall into the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope (which has been repeated criticism of his other female characters). It helps that TFIOS’ protagonist, Hazel Grace Lancaster, is the star of her own story in circumstances in which her conflict could very easily consume her character: Hazel Grace is sixteen years old, with terminal cancer and, as she says, is “okay” (11). She’s often more than okay: she is romantic, she knows how to savor life and how to be critical of it, she falls in love and she has adventures.

Her life is given a more passionate spark by her relationship with Augustus “Gus” Waters whom she meets in her Teen Support Group, but she is not consumed by love. She tries to balance between protecting herself and those whom she loves, and living for herself with the time she has left. She warns her family,

“I’m like. Like. I’m like a grenade, Mom. I’m a grenade and at some point I’m going to blow up and I would like to minimize the casualties, okay? I’m a grenade. I just want to stay away from people and read books and think and be with you guys because there’s nothing I can do about hurting you; you’re too invested, so just please let me do that, okay? (99)

When I finished the book, I had to resist the urge to throw it across the room as memories of my childhood experiences seeped back into my consciousness. Hazel’s experience was similar to my own as an early teen, as a twin sibling to my three-time cancer surviving brother, and I could not contain my rage and pain.

Sure, it wasn’t me who had the cancer, but one of the many things that TFIOS got right is that cancer is inseparable from the patient, and also from the family. Cancer grows and consumes and poisons family, too, and can destroy it. I’ve seen that happen to other families. Cancer seeps into every day of the family’s life in subtle ways, and lingers there. I lived through chemotherapy as much as my brother did.

TFIOS focused upon the lingering moments of cancer, which strangely enough are the moments that I remember most vividly: the ICU and its sticky floors to capture all of the dangerous dirt on the bottom of your shoes, the plastic walls, the nurses wearing Spongebob scrubs and smiles as beeping IVs are going off everywhere, cocktail medication appetizers with dinner at the same time every day. Yeah, I’ve been there. I got to be there again with Hazel just as I was there with my brother.

Yet, what is most beautiful about TFIOS is that it focused on the lingering living moments of having cancer. Despite having to carry her oxygen tank everywhere, Hazel lives for the sake of living, and that passion is always there, regardless of whether she is being snide in Support Group or spending time with Augustus. TFIOS is a constant reminder that those who are dying of cancer are still living. And not just living, thriving.

As Hazel points out:

There are infinite numbers between 0 and 1. There’s .1 and .12 and .112 and an infinite collection of others. Of course, there is a bigger infinite set of numbers between 0 and 2, or between 0 and a million. Some infinities are bigger than other infinities.[…] There are days, many of them, when I resent the size of my unbounded set. I want more numbers than I’m likely to get. (260)

That underlying fear of the day in which the infinite stretch of time we have becomes finite and conclusive is the heartbeat of TFIOS. Hazel and Augustus mention earlier in the story that “survivors live with uncertainty.” I revise this to say that survivors and their families live with uncertainty. Or perhaps, it should just be stated that families are survivors, too. Survivors have the uncertainty of the quality of their life as well as the quantity of their infinity. Recently, my brother has had some serious health problems as collateral damage to his cancer from 7 years ago, and coming home from school to my family in this state of home-hospital care was a slap in the face that we will always be uncertain about the quality of my brother’s life. We can try and we can help, and we can expand his infinite measurement of quality as well as quantity, but the uncertainty is always there. And, as Hazel’s speech reminds me, isn’t that the point of infinity? We can never actually know just how big it is.

I am angry that the book has made me confront this fear yet again. But it’s a beneficial anger: my anger is twisted with gratitude because while I confront this kind of thinking so frequently, this novel has made infinity’s uncertainty complex and valuable. Hazel has made every hundredth decimal place another good day—she has made the number represent the quality as well, the infinite measurement of goodness in life that is always there. I’m grateful that John Green’s novel brings this understanding to those who may not have had to ever confront it, and that it makes me confront it yet again. His book is a strangely rewarding kind of therapy that makes my experiences more tangible, more real and emotional. He has created a reminder of how much life there is in cancer—that the living cannot be suffocated by dying.

![[in]Visible Magazine](https://community.scrippscollege.edu/invisible/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2011/04/Invisible-Masthead-2011-Spring1.png)

No comments yet... Be the first to leave a reply!