Female Empowerment Through Health Workers Around the World

In Bolivia, 600 women die during childbirth annually; a pretty significant number for a population nine million (UNFPA). The indigenous population is particularly vulnerable. The nearest clinic can be far and even if a woman makes it to the clinic they are often treated like second-class citizens. One woman said, after three days of waiting, she was told by the doctor in the hospital to give birth by herself. Other women recall being tied to their beds so they couldn’t change their positions while in labor. In addition, relatives are not allowed to be in the room during the birth or even visit the hospital at all. Due to their maltreatment, many women have opted to give birth in their homes. This can be very dangerous if there is no skilled birth attendant present and has resulted in a lot of women dying during childbirth.

The situation in Bolivia is not unique. In addition to unsafe birthing conditions, in many countries women have limited access to educational opportunities, which impedes their ability to change their economic and social situations. Women suffer under gender discrimination that is, in some cases, condoned by both their culture and government. Women are left with very few tools to change their situation and must suffer under oppression that has profound effects on their health and well-being, as well as the health and well-being of their children and their communities.

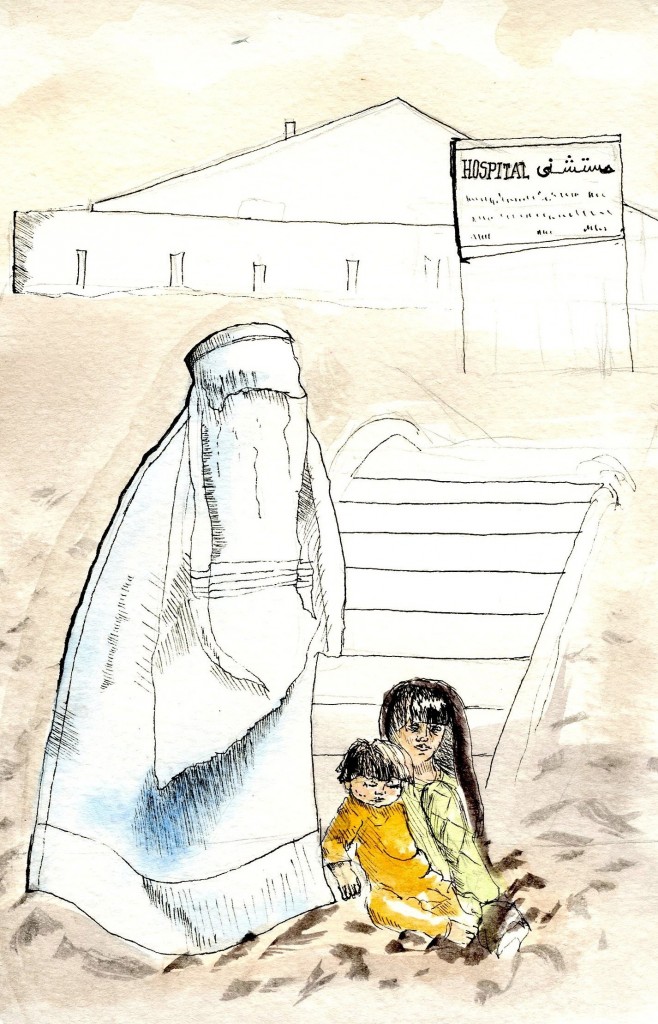

The situation in Afghanistan offers a striking example of the inequalities that women face. Under the Taliban, women were not allowed to go to male doctors, and they were forbidden to be educated, so it was almost impossible for women to receive medical treatment. Even though the Taliban no longer rule Afghanistan, many men, especially those living in remote villages, still do not allow their wives to receive medical care from men. In addition, the clinic could be four hours away, an impossible journey for a woman who is in labor and needs immediate medical attention, such as for complications in childbirth. A 2006 UNICEF study found that only 14 percent of Afghani women seek a skilled attendant while giving birth (Cooney). The rest give birth in their homes or other spaces outside of a clinic or hospital, which increases the risk of death during childbirth and of post partum complications.

Worldwide, the maternal and child health indicators are appalling. Every year, close to 350,000 women die during pregnancy or childbirth from complications that are, generally, preventable. Additionally, eight million children a year die before they reach their fifth birthday (Global Poverty Project). These preventable deaths have profound implications for public health and expose the injustices that exist in our world.

One inspirational solution that has been implemented to increase maternal and child health outcomes is the training of female community health workers. Initially, these community health worker-training programs were put in place in countries like Afghanistan, India, Ethiopia, and Bolivia. They were created because studies had shown that national statistics on the maternal and child health statistics of countries revealed a lot about a country’s economy, politics, and social inequalities that exist. These programs have been sponsored by the governments, NGOs or non-profit organizations that have noticed the need for attention to maternal and child health. Generally, women are the primary care takers of their families. Training these women enables them to build a healthy and productive workforce. Women also feel comfortable receiving care from other women, who may be mothers themselves and who have a personal understanding of the health issues that women face. The additional outcomes of these programs were that women received an education, were able to provide for their families, and were valued by men in their community because they possessed much needed skills. They felt respected, dignified and empowered to take control over their own health, the health of their families, and the health of their communities.

Female health workers, known as Accredited Social Health Activists in India and the Women’s Development Army in Ethiopia, have helped with family planning, health education, newborn health, nutrition, sanitation and vaccinations. They have also helped to deliver babies outside of clinics and hospitals. The results are impressive and inspiring. In Ethiopia the government struggled to bring quality health services to rural villages, to encourage pregnant women to seek quality preventative care and to keep babies healthy after they were born. Their solution was to implement a “women-centered” health system. Between 2000 and 2010 the child mortality rate decreased by half, contraceptive use quadrupled, and the total fertility rate went down (Ramundo). These programs are also sustainable because the trained health workers can in turn train other women in their communities. In Bangladesh, trained female community health workers with a little schooling and six weeks of hands on training were able to help reduce the rate of newborn deaths by one third. In Bolivia, the United Nations Population Fund has funded a midwifery-training program, which recruits women from remote rural communities and trains them at one of three rural universities. The hope is that after being trained these women will return to their communities and be able to perform births and educate women in their communities about maternal and child health in a respectful and culturally sensitive way. All evidence has shown that these programs not only improve the overall health of people in the country, but also help to empower women to take leadership roles in their communities and to realize their potential.

Molly Goldfarb is a sophomore at Pitzer. She is hoping to major in Spanish and Global Health. She will be studying abroad in Quito, Ecuador next semester.

Sources:

Ramundo, Kelly. “The Female “Army” Leading Ethiopia’s Health Revolution.” USAID. USAID, n.d. Web. 9 Mar 2013. <http://transition.usaid.gov/press/frontlines/fl_may12/FL_may12_ETH_HEALTHWORKER.html>

“Blogs | United States | Global Poverty Project.” Welcome | United States | Global Poverty Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013. <http://www.globalpovertyproject.com/blog/index/tag/9>.

![[in]Visible Magazine](https://community.scrippscollege.edu/invisible/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2011/04/Invisible-Masthead-2011-Spring1.png)

No comments yet... Be the first to leave a reply!